The China-Russia Space Partnership and Its Implications for the Security of the NAA

- CTG Global Analyst

- Apr 11, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: Nov 24, 2024

Konor Sajti and Rachel Kenny, CICYBER

April 12, 2021

Russia and China[1]

A Tuesday, March 9, 2021, Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), signed by China and Russia regarding plans for joint construction of the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) threatens current US domination in outer space. Through the lunar research station, Roscosmos, Russia’s space agency, and the China National Space Administration (CNSA), China’s space agency, will strategically place itself at the forefront of space development. The MoU details a bilateral project pursuing the sharing of experience about “space science, research, and development as well as the use of space equipment and space technology” between Moscow and Beijing.[2] The research lab will be constructed at the lunar south pole. The strategic location of the base will enable access to rare earth metals and other resources that will allow for scientific discovery.[3] Both Russia and China have demonstrated advanced proficiency in space research, and each nation currently has plans for significant lunar missions that they hope to promote through their ILRS.[4]

The Counterterrorism Group (CTG) estimates that this new partnership has the potential to seriously challenge the current international order and threaten a dangerous Cold War-like space competition between great powers. Smaller states are expected to line up behind leading groups in research and acquisition which will result in a shift of the balance of the currently US-led international system. CTG expects four major scenarios to evolve in the next decades: increased espionage activity by China, Russia, and the US; an escalating military and space competition between a Western and an Eastern alliance; the introduction of hybrid warfare into everyday interstate confrontations; and the reordering of the international legal system. These changes will affect the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) policies and strategies, which will experience the outbreak of new debates and the need for new approaches to the maintenance of international security.

Space cooperation between China and Russia may improve their preexisting strategic partnership, posing a greater threat to the West shortly. This position will enable them to emerge as alternatives to the current space leadership. A flexible international partnership between China and Russia will allow both nations to achieve their foreign-policy objectives while simultaneously making major strategic advancements in space. This is of significance to members of NATO, and the US in particular, because US intelligence has identified China and Russia as the greatest threats to US national security, and consequently to allied defense.[6]

The MoU comes after Russia fails to sign NASA’s Artemis Accords in October 2020, marking a Russian abandonment of the International Space Station.[7] The fact that China and Russia are willing to leave mature global cooperation projects for their initiatives signals that they perceive a change in the international strategic atmosphere and tend to value their partnership higher than the current US-led international one. This implies that cooperation between the two camps (NATO and China-Russia) will be less likely in the future. The Eastern allies will see their action less dependent on collective global actions, and consequently, less regulated by global interests. It is, therefore, likely that China and Russia will be less prone to cooperate internationally as long as they do not hold a stable hand on space projects, and thus, access to space.

China and Russia plan to provide—controlled—access to the base for other nations, once the joint construction is complete.[8] This is a clear intention to create an alternative to the US-initiated Artemis Project which outlined “a set of principles governing norms of behavior for those who want to participate in the Artemis lunar exploration program”.[9] This alternative also presents an opportunity for less advanced countries to enter space research with a goal “to set up a permanent human presence at the moon and refine technologies needed for future voyages to Mars”.[10] Plans for the ILRS strongly resemble those of the Artemis Program, showing that China and Russia wish to overbid their Western counterparts.

The moon is a strategic location for space development, not only because of its abundant resources but because of the efficiency of launching from the moon.[11] The 1967 Outer Space Treaty “bans the stationing of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in outer space, prohibits military activities on celestial bodies, and details legally binding rules governing the peaceful exploration and use of space.”[12] Even so, Russia has repeatedly demonstrated a blatant disregard for international laws and norms, as seen in the annexation of Crimea and a prolonged presence in Eastern Ukraine.[13] Additionally, China, Russia, and the US are developing space-based weapons, making the militarization of outer space a likely possibility.[14] Given this, Chinese and Russian space intentions should not be underestimated and assumptions should not be made about adherence to international law with regards to space developments.

A Chinese and Russian-led lunar research base that strongly resembles pre-existing American plans for moon exploration suggests an intentional threatening to the current world order. Should the Sino-Russian project offer better conditions for small states with increasing interest in space, it would not be a surprise that the hegemonic position of the US in space leadership starts losing ground. This could even result in significant Chinese-Russian domination of international organizations with powers to create regulations and laws, such as the United Nations (UN). Such shifts in authority and influence would in turn make a negotiated settlement of space competition—and potential conflicts—less and less likely. Hence, an Eastern alternative to the Artemis Project is a considerable threat to Allied dominance not just in space but in world politics of space as well.

The similarities between the ILRS and Artemis projects will likely incite the reemergence of a Cold War-style space race, now with China and Russia on one side and the US and its allies on the other. Russia and China have developed relatively stable relations in recent years, especially because of the countries’ mutual disdain for America and democratic ideals. However, the current relationship between Russia and China can be most accurately described as a strategic partnership, rather than a true alliance, because Russia doesn’t have enough to offer China to make the alliance valuable for China. This is particularly true in the economic sector, as Russia’s stagnant economy and China’s flourishing one are visibly incompatible. A flourishing partnership in space may serve as the final contributing factor that promotes a true alliance between China and Russia. This partnership in outer space research is significant because China will have the opportunity to access Russia’s historically strong expertise in both the scientific-technological and political-strategic aspects of a space competition with the US. Subsequently, Russia will also be offered a chance to solidify a more firm alliance with China that may extend even beyond space, into a more general, political alliance as an opposition to the US. Thus, the cooperation is likely to further the already good relationship of China and Russia, and may change the landscape of global space research by relocating resources and attention from the traditional US-Russia axis to a more equally distributed global theater; although the measure of this shift is unpredictable at this early stage.

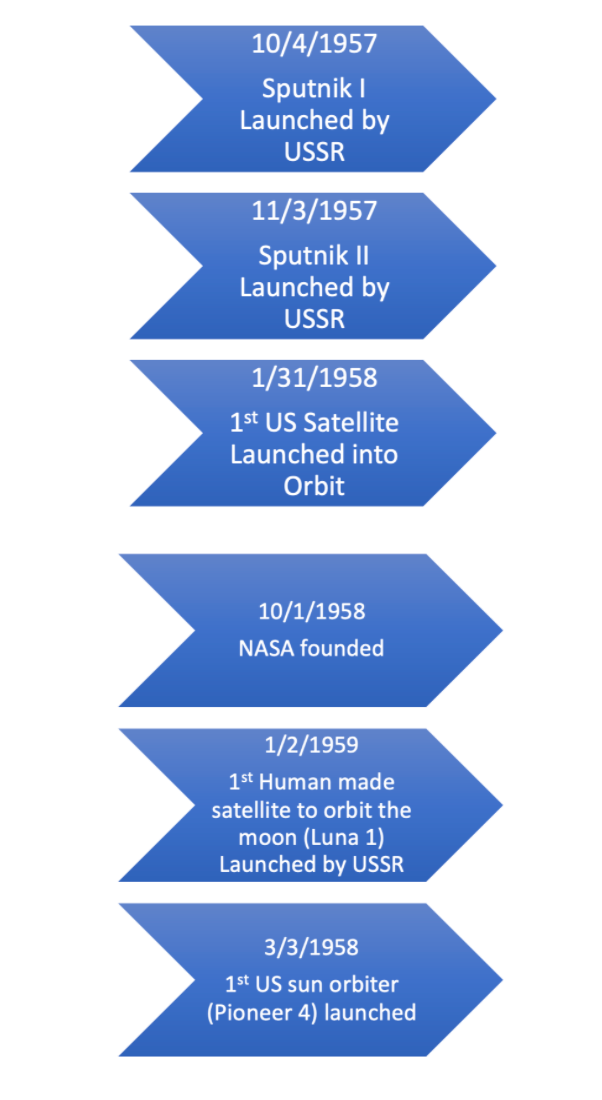

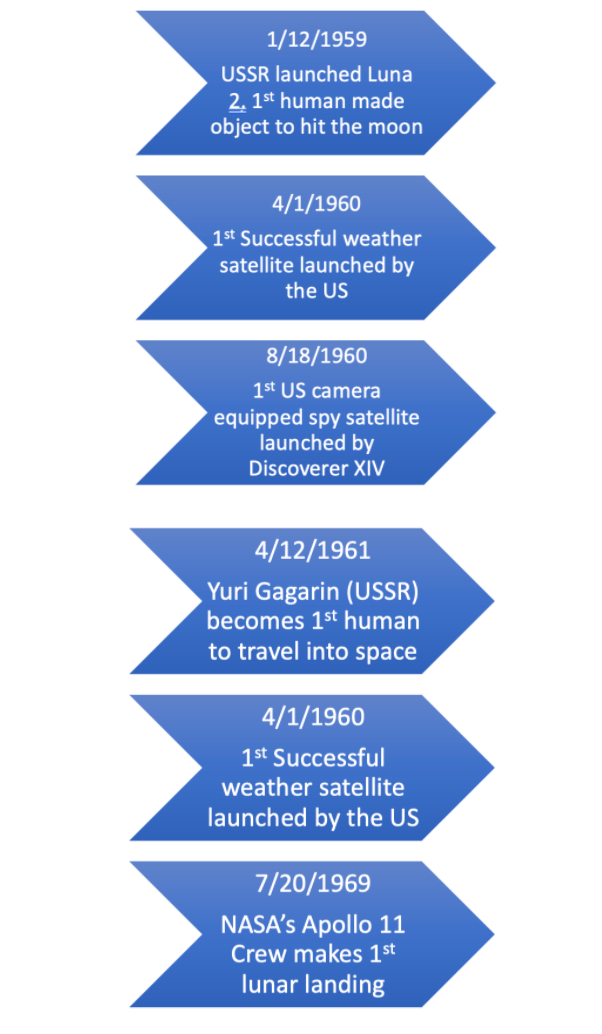

Since the 2014 Euromaidan demonstrations and the beginning of the civil war in Ukraine, cooperation between the US and Russia has been upheld virtually only by their joint information sharing and research programs, something that is expected to increase with the new Chinese-Russian initiative. This strategic shift may cause the deterioration of relations between the US vis-á-vis China and Russia, resulting in an even stronger Chinese-Russian alliance in the forthcoming years. US President Biden has already demonstrated his intentions to take a stronger position against Russia in his recent expulsion of 10 Russian diplomats and sanctioning of 32 Russian entities and officials, which is expected to further increase tensions between Washington and Moscow.[15] The US-Russia relationship has a long history of competition and disagreement, and Cold War ideology is often seen today in Putin’s foreign policy. During the Cold War, the US and USSR engaged in an outer space competition that came to be known as the space race. The reemergence of global interest in space development, particularly in the wake of the Artemis Accords and the MoU concerning the ILRS suggested the potential for a modern space race between the US and its allies, and Russia and China. The timeline below illustrates some major developments of the space race, as the US and USSR worked tirelessly to outperform the other in the realm of space. The space race was effectively won by the US after the first lunar landing, though from 1957 to 1969, extreme technological progress was made by both nations.

Figure 1: Timeline of Major Developments in Space Research by CTG’s CICYBER Team

The periodicity of major technological developments suggests a pattern that may forecast a similar periodically changing balance in the new space competition. Past experiences thus provide a reason to believe that this new rivalry will be somehow balanced with peaks and valleys for both sides. Great powers are expected to make strategic moves in this context to change the length of periods when they dominate the system. This will be achieved through enhanced intelligence collection to reduce differences in technological development, and offensive attacks through proxies to damage or distract the other one’s efforts and investments. These offensive strategies are likely to involve means of hybrid warfare, such as cyberattacks, sabotage, and the breaking of supply chains. According to the director of the Pentagon's Space Development Agency, these types of attacks are more dangerous for satellites and other space technology than conventional missile technologies or weapon systems because they are far less costly in terms of money and required human input.[16] It is recommended that national security agencies and space research institutes develop advanced information technology systems to prevent and counter these kinds of hybrid threats. Future space and aerial technology will need, for instance, leading encryption and transmission technologies, and all this in revolutionary forms of nano hardware and supercomputers.

This increased demand for technologies that are capable of operating in the tough conditions of space will affect national economies too. Governments will recognize the importance of state-sponsored and state-motivated private research projects, such as Blue Origin, Boeing, or SpaceX in the US, and will heavily invest in space to win the international contest. In close relation to this, it will be a new challenge to counterintelligence agencies to address new types of economic espionage and the semi-legal outsourcing of innovations to foreign adversaries. Leading companies may even establish their intelligence units to prepare for, deter, and defeat incoming threats to their internal security and business secrets. How the dynamism and share of private and public security services and research will change is a question of the future, but it is certainly a noteworthy aspect of the evolving situation which will have to be monitored and integrated by governments if they wish to hold control of their national resources.

CTG has assessed the potential scenarios concerning future security challenges. These are presented in Figure 1 below:

“Figure 1: Four Scenarios to Predict the Future of International Security Strategies”

These scenarios are not necessarily interlinked, although, it is expected that some of them would trigger others as events follow each other. For example, Scenario 2 almost exclusively requires Scenario 1 to happen since it is somehow a prerequisite for military competition to be preceded and assisted by intelligence. Hybrid warfare (Scenario 3) is likely to occur because it is cost-effective, easy to execute, has a great impact, and is relatively defensible against counterattacks. Scenario 4 is considered to be unlikely judging now, as an international framework for cooperation would require mutual trust and understanding among competing parties, as well as a new institutional structure to govern changes and lead negotiations. This seems to be very unlikely to happen shortly for the complexity of the issue, its monetary and political requirements, and for what we see in China’s and Russia’s turning away from these kinds of joint projects. In conclusion, although the list is not exhaustive and may even change or broaden over time, it provides a good overview of the four major challenges that are expected to risk international peace and stability in the forthcoming decades. Thus, CTG highlights (1) the importance of intelligence and counterintelligence operations with regards to the space competition; (2) the possibility of a new Cold War-like great power competition, now perhaps with a multipolar system, with new actors and more dispersed threat nests which would require a different strategy from that of the Cold War; (3) the possibility and relevance of hybrid warfare as a primary means of interstate confrontation; and (4) a challenge to the current, UN-centric international liberal order to maintain peace, resolve conflicts and enhance mutually beneficial negotiations for competing powers. These scenarios are all likely to happen with different measures of certainty, where certainty refers rather to the blurriness of our picture of the scenario than to the actual probability of it. Thus, Scenario 1 is quite foreseeable with well predictable characteristics and requirements, while it is less clear what Scenario 4 will include.

As for countering the threat of a new era of turbulent change and conflicts, measured preventive and reactionary steps are required from Western-allied countries. In this regard, CTG encourages NATO countries to gather all-source intelligence on Russian and Chinese space projects through conventional espionage. Additionally, the US, the EU, and NATO should encourage and welcome individual and private initiatives that monitor and examine the new Chinese-Russian alliance because these sources may reveal information that could otherwise be hidden from state officials.

Deterrence strategies from both the US-NATO and China-Russia sides are expected to occur, very likely turning into an arms race. This could function as deterrence for all involved parties not to expand too rapidly and aggressively. However, the arms race would also mean a significant delimitation of strategies for all countries directly or indirectly involved in the arms race, which would, in turn, reduce the probability of peaceful coexistence in the forthcoming decades. An efficient deterrence strategy might be a competition for information and a good position in the emerging international legislative agenda. As a result of growing interests in outer space, states will likely seek to gain information advantage on each other by spying and enhance research activity. States will also realize that an arms race is avoidable only through international agreements and legislation, which will require the updating of existing UN resolutions on the use of space in addition to creating new legislation regarding extraterrestrial activities and the use of commons in extraterrestrial space and objects.

CTG will also contribute to this new security complex. Our geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) team will seek satellite imagery in known or suspected Russian and Chinese space research sites to gain intelligence on facility and technological developments. Additionally, CTG’s CICYBER team will monitor Russian and Chinese intelligence activities within NATO and EU countries to estimate the intelligence requirements and strategies of the new alliance. CICYBER will also observe the US and Allied attempts to gain information both on terrestrial and extraterrestrial sites of Russia and China, as well as examine the relevant technological developments to forecast possible state strategies and international competitions. Finally, CTG will continue collecting intelligence on Russian and Chinese space projects, military movements, and intelligence activity to alert Allied countries and clients of threat when it is expected to reach a critical point. CTG will inform its clients about the developments of the situation to raise awareness among policymakers and provide strategic intelligence to national and international decision-makers.

_______________________________________________________________________ The Counterterrorism Group (CTG)

[1] Russia and China by Google Maps

[2] Chinese Embassy in Russia, Twitter Post, March 2021, https://twitter.com/ChineseEmbinRus/status/1369362300197539847

[3] Goswami, Namrata. “The Strategic Implications of the China-Russia Lunar Base Cooperation Agreement”, The Diplomat, March 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/the-strategic-implications-of-the-china-russia-lunar-base-cooperation-agreement/

[4] Ibid.

[5] Myre, G. “ Biden's National Security Team Lists Leading Threats, With China At The Top”, National Public Radio, April 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/04/13/986453250/bidens-national-security-team-lists-leading-threats-with-china-at-the-top

[6] Clark, S. “Russia looks to China as new space exploration partner”, Spaceflight Now, March 2021, https://spaceflightnow.com/2021/03/15/russia-looks-to-china-as-new-space-exploration-partner/

[7] Episkopos, M. “The New Space Race: Russia and China Want a Joint Lunar Space Station”, The National Interest, March 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/new-space-race-russia-and-china-want-joint-lunar-space-station-180208

[8] Foust, G. “Eight countries sign Artemis Accords”, Spaceflight Now, October 2020, https://spacenews.com/eight-countries-sign-artemis-accords/

[9] Clark, S. “Russia looks to China as new space exploration partner”, Spaceflight Now, March 2021, https://spaceflightnow.com/2021/03/15/russia-looks-to-china-as-new-space-exploration-partner/

[10] Goswami, N. “The Strategic Implications of the China-Russia Lunar Base Cooperation Agreement”, The Diplomat, March 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/the-strategic-implications-of-the-china-russia-lunar-base-cooperation-agreement/

[11] “The Outer Space Treaty at a Glance”, Arms Control Association, October 2020, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/outerspace#:~:text=The%201967%20Outer%20Space%20Treaty,exploration%20and%20use%20of%20space.

[12] Gilmore III, J. “Ongoing Violations of International Law by the Russian Federation in Ukraine”, U.S. Mission to the OSCE, December 2020, https://osce.usmission.gov/ongoing-violations-of-international-law-by-the-russian-federation-in-ukraine-3/

[13] Episkopos, M. “The New Space Race: Russia and China Want a Joint Lunar Space Station”, The National Interest, March 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/new-space-race-russia-and-china-want-joint-lunar-space-station-180208

[14] US imposes sanctions on Russia over cyber-attacks, BBC, April 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-56755484

[15] Erwin, S. “DoD space agency: Cyber attacks, not missiles, are the most worrisome threat to satellites”, Space News, April 2021, https://spacenews.com/dod-space-agency-cyber-attacks-not-missiles-are-the-most-worrisome-threat-to-satellites/